Lababidi links Gaza clearly to other genocides, passing through Elie Wiesel to the memories of genocide at the hands of the American government for the Lakota and Dakota Sioux at Standing Rock.

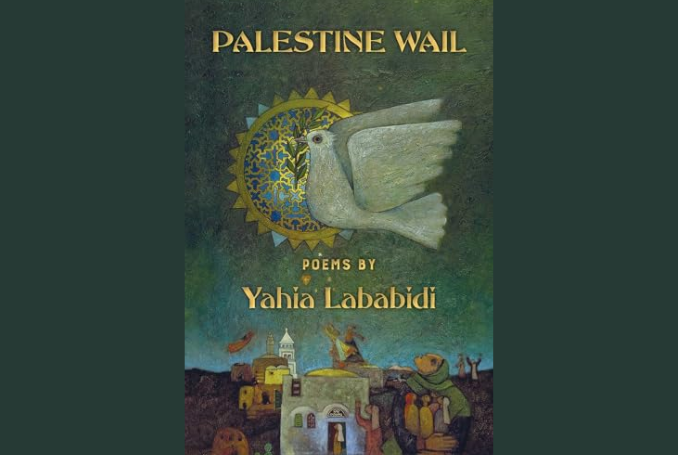

A slim book, weighing in at less than 100 pages, Yahia Lababidi’s Palestine Wail, is a luminous collection of poetry and essays, leading us through the backroads of grief and offering us glimpses of hope as he describes moments of daily life in Palestine -memories, and culture while urging compassion and an open heart.

An Arab American poet with roots in Palestine, Yahia Lababidi is clearly in grief for Palestine and now, Lebanon. His is a monstrous task- to bring the voices and vision of those brutally ravaged and silenced, forward for our consideration.

Lababidi is a prolific poet – many of the poems in this collection have debuted elsewhere – in Scholar, in Electronic Intifada, Tell Me More, and NPR, among other places.

But, as Lababidi explains, he has sought solace in art and in writing. It is this solace he offers, in turn, to the reader through clearly drawn imagery and deftly chosen words.

Divided into sections with titles such as “Unbearable Casualties” and “On A Far Shore,” the poetry in Palestine Wail is bookended by two essays with broad-ranging references that link the current situation in Gaza to other places and people.

Lababidi’s essays bound out of the gate with unexpected vigor and clarity, setting and reiterating the tone of the work between them. The book is fittingly crowned with a beautiful painting by noted Palestinian artist, Sliman Mansour, of a Palestinian mother sheltering her children in her arms as she looks up at a resplendent dove of peace.

The first essay, “Wounds as Peepholes,” bravely names what is happening in Gaza as a genocide at the hands of the Israeli government. Despite the risk (another publisher passed on the book because of the reference), Lababidi unblinking names the act, echoing both the UN Convention on Genocide (of which both the US and Israel are signatories) and Dr. Gabor Maté.

Lababidi links Gaza clearly to other genocides, passing through Elie Wiesel to the memories of genocide at the hands of the American government for the Lakota and Dakota Sioux at Standing Rock. It is these genocides as well as the Armenian Genocide of the early 20th century, which formed the backbone of the Final Solution and now find their echo in the events in Gaza.

Lababidi invokes other writers, other voices such as the Persian poet Rumi and the Lebanese writer, Khalil Gibran to lend fullness to his grief. But Lababidi also uses this opening essay to encourage the reader to be open to the thought that wounded people (those acted against), often turn that violence on others and to reflect that our modern societies are often wounded both by what was done to us and what we have done in return.

And yet, Lababidi does not leave the reader adrift amidst pain and conflict. In the poetry that follows, he generously loans the words by which to grieve that which was once unimaginable – the mediated daily now made monstrous. And thus, he shows us the way to witness, without being so overcome that we are consumed by what we had not thought possible.

While his lines are often delicate and descriptive, his poems are no shrinking flowers. They are heir to the Sufis and their brilliant metaphors, standing on the shoulders of the sophisticated styling of classical Arab poetry. But the emotion, the outrage, and the heat- all his.

Flowers, trees, birds, music, and sunshine, break through the fog of despair that lingers over the collection. It is no accident that Lababidi invokes nature, almost like a major component of hope and healing. The garden, a collaboration with nature, is stronger than the urbicide – the murder of urban centers. Olive trees that have stood for centuries, flowers that bloom every season recall the beauty and magic of Islamic gardens which themselves serve as invocations of Paradise.

Even the birds, flitting through the poems carry meaning on their wings. Messengers of hope, evoke Marcel Khalife’s moving song, “Asfour,” about the fear and desire for freedom of a little bird, which is a stand-in for the frightened children of Palestine.

At the same time, Lababidi is kindness itself. He does not harangue the reader, but, like Rumi, bids her/him to witness.

As famed Palestinian poet, the late Mahmoud Darwish, has written, “Every beautiful poem is an act of resistance.”

In the first section of poetry, it is clear that Lababidi has chosen to resist – to resist paralyzing despair, erasure, censure, and apathy. What is happening to Gaza is deeply personal to him. He invokes a beloved grandmother, Rabiha Dajani, who was forced to flee her town during the Nakba, or Catastrophe of 1948, while at the same time, he faces deep disappointment in his current country, the US, which pursues protestors while it sells the horrific weaponry of mass murder.

Lababidi also does not hesitate to address the elephants in the room: who or what deserves our care and pity? In “Why Care?” he suggests it is because one is privileged not to share a similar fate while the larger elephant- why empathy for Ukraine and not Gaza? – looms over this entire section

But he does not let the reader off lightly. In “Say Something,” he prays for a conscious witnessing:

“say humanity under the rubble…

say Lord, forgive us

the enormity of our sins.”

(pg. 36)

But it is to those protesting that Lababidi consecrates deeper thought. Go to the protests, he says,

“Bless the young for reminding us there is no looking away

no foreign soil

no Others.”

– Columbia University (pg. 9)

And, in fact, that is Lababidi’s point – to see the infinite connections between people and peoples and to see that in wounding and abusing one, we wound and abuse ourselves.

In his Afterward: Of Poetry and Resistance, Lababidi’s voice takes on a tone of defiance and challenge. Gone is the despairing artist of the early poetry. The energy that infuses the later section of his poetry comes full to the fore here. The obscenity of the West’s collaboration in Israel’s genocide of men, women, and children has been named. And the artist wields his art and his verse like a protective shield.

“Artists are dangerous,” Lababidi says. And he evokes the patron saints of resistant writers, Dr. Refaat Alareer, targeted by an Israeli strike in December 2023, and Ghassan Kanafani, a prolific Palestinian writer, assassinated by the Mossad in 1972.

But it is through art, words, and music, says Lababidi, that we must find common ground, lest we be condemned to wander, meditating on sin, revenge, and the loss of our collective soul.

To write of such a human catastrophe as it is happening is difficult, but Lababidi is quite clear – to say nothing, to turn away is to deny a common humanity – but by reading work such as this, bearing witness through words and images, hope finds a refuge, and the reader learns there are no “Others,” just “we.”

– Rebecca Romani is a freelance arts writer who often writes about MENA art and culture in the United States. She has been published in several newspapers and magazines. She contributed this article to the Palestine Chronicle.