“I believe that the beginning of the real work of liberating Palestine is the appearance of the Palestinian fida’i who carries the rifle, gun and grenade, who crosses the wires and existing borders created by Israel.” – Umm Kulthum

A documentary camera takes a running shot of an expanse of land, pockmarked with barbed wire and concrete walls. UN military vehicles come into view along a road dotted with fruit trees, growing thicker to reveal a landscape of olive groves.

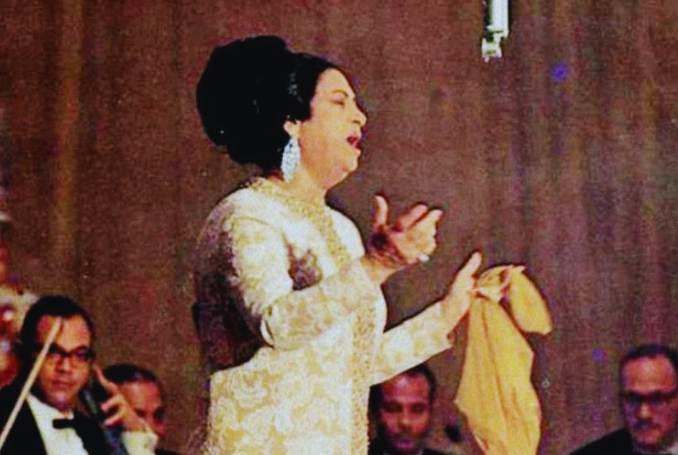

Beyond an enfenced frontier, endless green, farmlands, rolling hills touching the clouds. To strings and woodwind, an unmistakable voice sings, “Now I have a rifle, take me with you to Palestine.” The film, Fedayin, on French-confined Lebanese political prisoner Georges Abdallah. The voice, Egypt’s fourth pyramid, Umm Kulthum.

Fifty years on from her death on February 3, 1975, “al-sitt,” the grand lady of Arab song, retains her influential status among generations of music lovers. Her performing career spanned five decades and around 320 songs, which defined eras, evolving styles, and artistic revolutions. Built around the participatory tarab genre, the music was largely romantic in content but also gave voice to the struggles and hopes of the Egyptian and Arab masses.

This arguably held even greater truer for Palestine. Vocally supporting the cause and leading fundraising for the resistance after 1967, the relationship of Umm Kulthum to the Palestinian people had deeper roots, reaching back before the 1948 Nakba. Her singing and solidarity are remembered by Palestinian musicians joining their people in collective resistance today.

Nowhere is this connection stronger than in Gaza, where the music of Umm Kulthum reverberated in the memories of generations of performers and music lovers. Oud player Sarraj Alsersawi affirms that “almost everybody in Gaza listens to Umm Kulthum daily, in cafes, barbershops, taxis, by the sea,” singling out the al-Sharq al-Baqa and Nuweiri cafes:

“At any break in the war, we would go directly to the coast and relax to the music of Umm Kulthum, when at 6 pm Ajyal FM would have its Umm Kulthum hour, and we would hear this in taxis and everywhere else.”

Listening to her songs in Gaza, he thinks, made their effect “much more powerful” in the embrace of the music at street-level, rather than individualized online streaming: “When her voice comes from the speaker at the vegetable market, or the barbers or the taxi, it gives it a different flavor.”

Hearing “love and politics mixed with poetry and melody,” Reem Anbar found in Umm Kulthum a “music that changed my life,” while learning oud in Gaza City. Her image as a strong woman in a male-dominated world spurred Reem on during an environment of the al-Aqsa Intifada, with “concerts everywhere” and new generations striving to contribute.

“I have played many of her songs, in times of joy and in war, so I guess she has become my comrade in all circumstances. I don’t know how I came to memorize all of the rather difficult and lengthy words and music, but what really mattered to me is the meanings they expressed through the captivating spirit of tarab melody.”

Vocalist Rawan Okasha and multi-instrumentalist Said Fadel also grew up in Gaza City. Rawan remembers Umm Kulthum coexisting with the “old greats, not to mention our important traditional and revolutionary songs.” The first song she learned to sing was “Lissa fakir” (Do you still remember?), a tale of love, loss and torment. “My father would play it on oud and I’d copy the singing. I learned nearly all of her songs but “Lissa fakir” was the first.” In a similarly creative household, Said recalls communal jam sessions:

“My mother, siblings, and grandparents too, we’d sit together every Thursday and learn tarab songs together, Umm Kulthum, Abdel Wahab, like a family gathering, and then we’d start playing. Everyone would encourage each other—there was no “don’t play this,” or “play quietly”; no!”

“Beautiful Memories” in Music and Politics

Born in the village of Tammay al-Zahayra in the Nile Delta region of Daqahliyya, a young Umm Kulthum began singing as a child alongside her brother Khaled, cousin Sabir and father Ibrahim, a local sheikh.

Exhibiting confident vocal technique and memorizing the Quran, she was brought into Sheikh Ibrahim’s religious singing ensemble, performing at small functions across the province. Spotted by maestro Abu al-‘Ila Muhammad, who took her under his wing, a teenage Umm Kulthum moved with her family to Cairo in the early 1920s and quickly gained a following and recording contracts that would establish her as a phenomenon. She would go on to work with Qasabgi, Sunbati, Abdel Wahab and other masters of Arab song, steadily establishing herself as an international phenomenon.

As her singing began to resound via the gramophone records and cafes of the region, Umm Kulthum naturally found herself in the cities of Palestine, then under British colonial occupation. Filastin newspaper published adverts about her and her music, announcing a hotly anticipated tour. Palestinian vocalists recorded versions of her songs, sometimes immediately after her records had been released. She came to perform in Palestine for the first time in October 1931, arriving in Haifa during a period when she also toured Syria and Lebanon.

In Haifa, she arrived to a huge reception of enthusiastic audience members, intellectuals and notables. She was joined by oud virtuoso Muhammad al-Qasabgi and qanoun player Muhammad al-’Aqad. Also appearing at theatres in Yafa and Jerusalem, Umm Kulthum would tour Palestine twice more, playing consecutive full-house shows in the same three cities in June-July 1933 and May 1935. Musician and diarist Wasif Jawhariyyeh wrote of an “overwhelming” turnout during her first visit to Jerusalem, where an oversubscribed crowd almost passed out with excitement.

Research by Nader Jalal shows that her concert at Yafa’s Bariziyana Cafe theatre in July 1933 brought audience members from Gaza, Lydd, Ramleh, and Nablus to hear her voice. After one show she reportedly kissed the head of Palestinian oud player and child prodigy Ruhi al-Khammash. By all accounts, she exhibited a strong and exacting personality, directing rehearsals and shaping the work of her composers and lyricists.

She would also lead the Egyptian Musicians Union and held several positions under the Nasser government after the revolution of 1952. Whilst in her early years Umm Kulthum had sung many taqatiq, qasa’id and other song forms, her repertory during this period came to include patriotic and anti-imperialist songs.

Songs with stanzas of “Lil-sabri hudoud” (Patience has its limits) and “‘atini hurriyyati ‘atliq yadayya” (Give me my freedom, unchain my hands), the latter in “al-Atlal” (The ruins), were interpreted by many as having liberationist content. Others, like “Wallah zaman ya silahi” (How long it has been, my weapon) became official anthems of pan-Arabism.

The 1967 Naksa and Zionist defeat of Arab armies influenced Umm Kulthum greatly. In a period when the Palestinian revolution reemerged as a rising regional force, she toured widely, raising funds for the armed struggle.

She came to see her goals as beyond music, for “liberating the dear occupied lands, cleansing Palestine of the stain of Zionism, and returning Arab Palestinians to their homeland.” In tune with the socialist ideas emanating from international struggles, she also considered “singing for the sake of Vietnam, its people, and its future.”

The death of Umm Kulthum in 1975 saw four million people flock to her funeral procession in Cairo. Five decades on, across borders and histories, her voice continues to be heard. Though working-class Egyptians hunger to be part of the Palestinian fight, Egypt today is a far cry from the days when singing for solidarity formed part of a pulsating movement.

As Sarraj Alsersawi points out, “These songs of Umm Kulthum were produced at a time of war, tied to the fate of Abdel Nasser, Arab nationalism and the republic, which included Syria at the time.” Sheikh Imam and other revolutionary artists carried the baton leftwards and kept Palestine center-stage, but this message now faces erasure.

With family in Gaza, Reem Anbar reflects: “Umm Kulthum gave beautiful memories that have remained with me from childhood, of our home which is now destroyed, along with books and cassettes of her music.” In Gaza at least, remembering the past means a fight for the future, with glimmers of promise chiming with Umm Kulthum’s call for the right of return for displaced Palestinians.

(The Palestine Chronicle)

– Louis Brehony is a musician, activist, researcher and educator. He is author of the book Palestinian Music in Exile: Voices of Resistance (2023), editor of Ghassan Kanafani: Selected Political Writings (2024), and director of the award-winning film Kofia: A Revolution Through Music (2021). He writes regularly on Palestine and political culture and performs internationally as a buzuq player and guitarist. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.